My sister got me the Grecian Computer Brainteaser Puzzle for Christmas. My first thought was: “Should I write a program to brute force it or go the cryptanalysis route to find a weakness?” After a bit of playing, I didn’t expect to have the time I would need to look into the positional relationships to the level necessary for a manual solution. I then pivoted to think about how I would solve it programmatically.

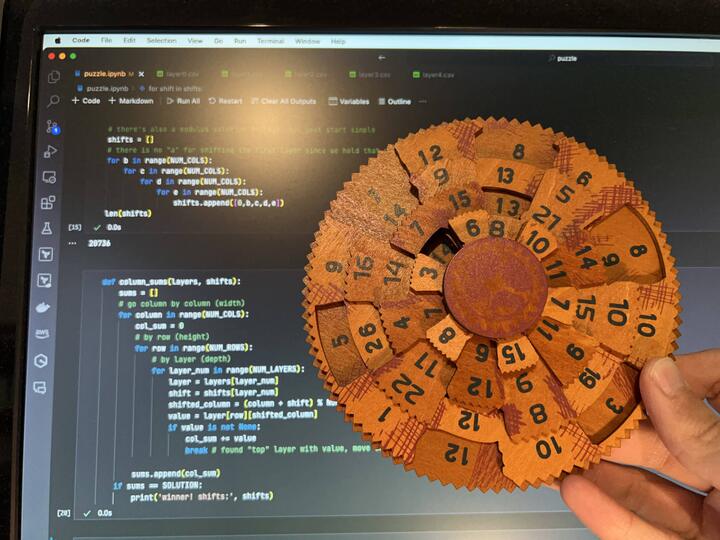

Here is my Python notebook solution.

My math professor used to have a saying about the “brute force and sheer ignorance” approach. Unless the computational complexity proved too much, that was going to be my first angle of attack. I would run through each of the possible shifts, add up the numbers in each column, and print out if there was a match.

I followed these steps:

- Draw up a small 4x4 sample matrix solution on paper.

- Decompose it into 5 layers (also on paper) since the real puzzle had one more layer than rows.

- Enter these rows into 2-dimensional sparse arrays with

Nonefor when you should “look through” to the next layer down. - Write the algorithm.

- Run it, expecting to find a solution on the first attempt since it was already aligned.

- Shift the columns around, expecting to still find one solution partway through the brute force search.

- Write the code to read the matrix definitions from a set of CSV files.

- Verify CSV ingest method by entering my shifted 4x4 matrices.

- Enter the real set of five 4x12 matrices.

- Run the search and verify the solution!

I did not know if I would succeed on the first try, so I kept the code unoptimized to allow for the easiest debugging possible. For example, I materialized a list of shift combinations instead of using

divmod()

to calculate each one on the fly. I kept the actual sums as a list rather than just counting the number of target value matches. I expected to have a typo somewhere in my CSV files and only get 10 or 11 matches out of the full 12. If my optimistic run of the program didn’t yield a solution, I planned on backing down the threshold to print state until I got some results. Then I could align the physical dial and check if I entered a value incorrectly.

One interesting finding on the first pass was the number of solutions equaled the number of columns with all the shifts incrementing together. This was due to the fact that rotating the full puzzle a slot is still solved. I realized this during my small test run and adjusted the shift generation code to “hold one disk steady” while rotating the remaining 4.

I was surprised at how quickly the code ran considering it was O(n^7) == height ^ width ^ depth ^ 4 shifts. I was also surprised to find the solution without having to add any additional debugging! It was a very fun experience solving the puzzle. It ended up taking me 3 hours with much less frustration than if I had tried doing it manually! Thanks again to my sister for a great Christmas present idea!