We all have errors. What is your nominal error rate? Does that include customer errors or just internal errors? Is everyone on the same page about that?

How can we get the highest signal fault attribution data when we’re looking at metrics in our APM tools? We can break the challenge down on two dimensions.

- Error reporting precision: More granular status classification than HTTP codes get you by themselves, including the ambiguity of fault assignment. This also covers APIs that only use a single HTTP code, like industry-specific XML APIs that report custom status in the body.

- Error reporting accuracy: Propagation of and voting on fault assignment as requests travel through the depth and breadth of a microservice call graph.

Solving both dimensions reaps several benefits.

- Straightforward, readable monitoring queries. Fault assignment is already pre-computed, avoiding the need for brittle queries. Query conditions stay bounded as system size and failure modes grow.

- Business-approved classification definitions lead to understandable SLOs that resonate.

- Your choice of rough or fine-grain status buckets is available depending on the monitoring or reporting use case. Use rough grain for more anomaly detection statistical power or fine grain for a jump start on troubleshooting.

Classification

Classifying errors in deeper granularity increases precision. Sometimes you don’t want precision, like when you need more statistical power in anomaly detection monitoring. In those cases, the sub-classes can be combined back together into higher level classifications: success, our fault, customer’s fault. Maintaining more precise, per-request outcomes is helpful for troubleshooting or assessing incident impact.

Here was a quote from David Reaver in his talk How Stripe achieves five and a half 9s of availability, Re:Invent 2024 that is a useful data point how some organizations are moving beyond just using status codes. I would be curious to learn more about Stripe’s error classification framework.

We don’t solely rely on standard HTTP response codes to decide if a request is successful or not. Classically 200 is “that’s great,” 500 is “error and our fault,” 400 is “error and your fault.”

That’s too simple. We don’t do that. There are lots of legitimate 400 responses that are kind of routine and expected. You can’t just page on them all the time.

Examples:

404s on a system of record might have a different level of confidence than 404s on a derived data system. It would be nice if we could engineer all systems to be like

KMS grant tokens

and overcome eventual consistency, but in reality, sometimes we have to deal with non-ideal scenarios. It can be helpful to recognize and codify a particular system’s resource not found as an unclear attribution error instead of just assuming it’s the client’s fault. We can follow up with automation that checks if the item eventually shows up or correlate with processing/replcia latency metrics coming out of that system to get the full picture and raise the necessary alerts.

400 errors can also have a large semantic range. One client might send a request with North Carolina instead of NC for an enum value and be rejected immediately. Another might fail further down the request path if North Carolina doesn’t yet have regulatory approval for a product. Both failures are based on the customer-provided data. We can classify them more precisely into customer data validation error and customer data error.

Things can get tricky on classifying faults with conditionally required data. A business rule upstream could necessitate an additional piece of data only sent in 1% of circumstances. Is this a validation error or a calculation error? This is why, irrespective of which classifications your business chooses, they must be defined precisely. The classifications provided here are a starting point to jog ideas. Each organization should agree on a set that covers all their incoming transactions. The organization can then have a shared nomenclature, leading to more accurate communication.

Voting

The second goal of this proposal is to increase error reporting accuracy via delegating and voting. Whether you have microservices, a modular monolith, or any other design, there will be abstractions. These abstractions shield complexity but also shield information. Ultimately, we want to know the status of the final response to the customer, but the high abstraction component last in line on the response path might not know the details of why a failure occurred. The solution is a structured and predictable way to pass and merge status from all services in the call graph.

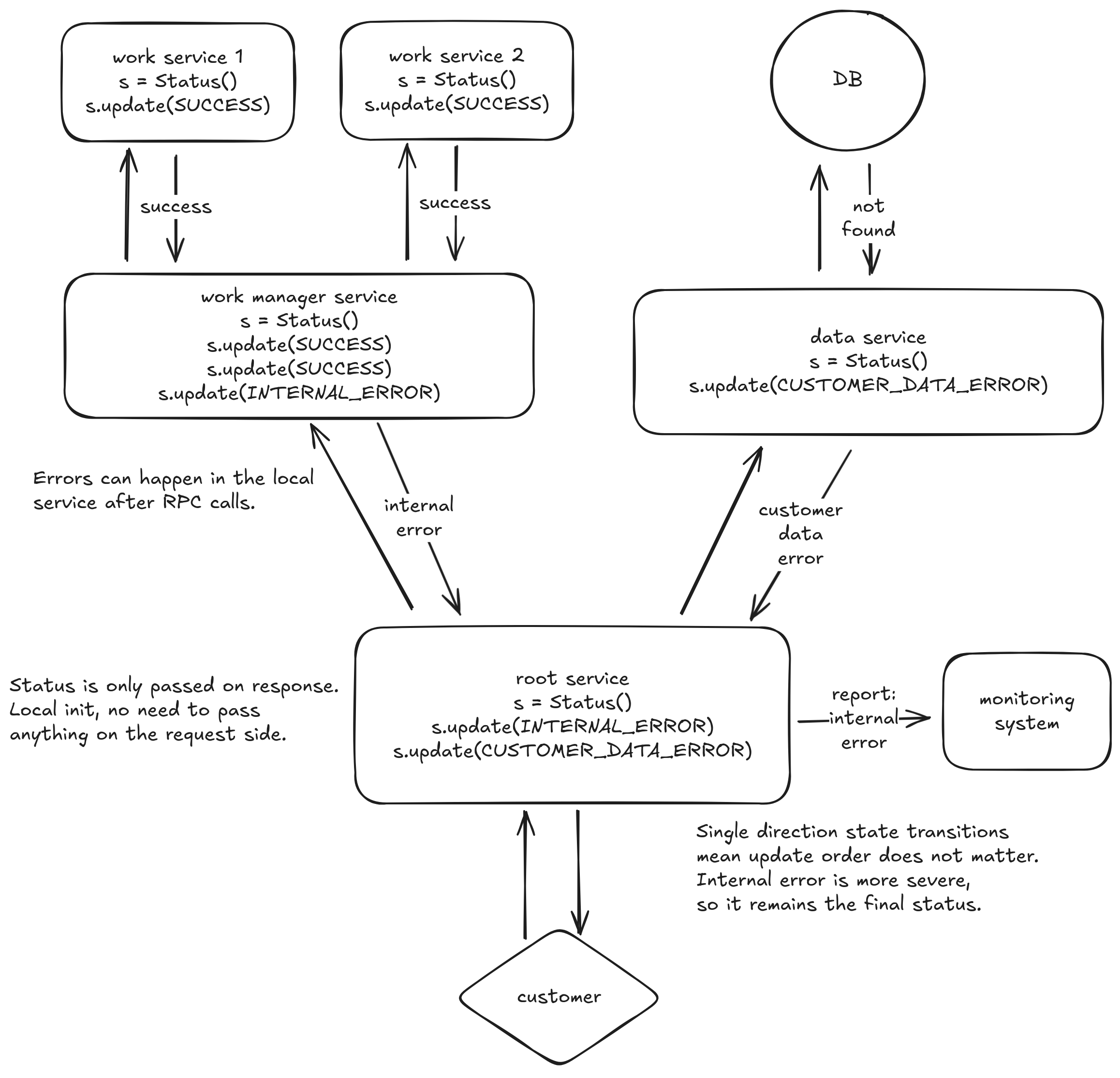

Errors can occur at any level of the call graph and before, during, or after work.

- Before: a request comes in, validation fails, and immediately returns.

- During: an upstream service or DB is unavailable.

- After: multiple DB or RPC calls are made, then an error occurs merging the results.

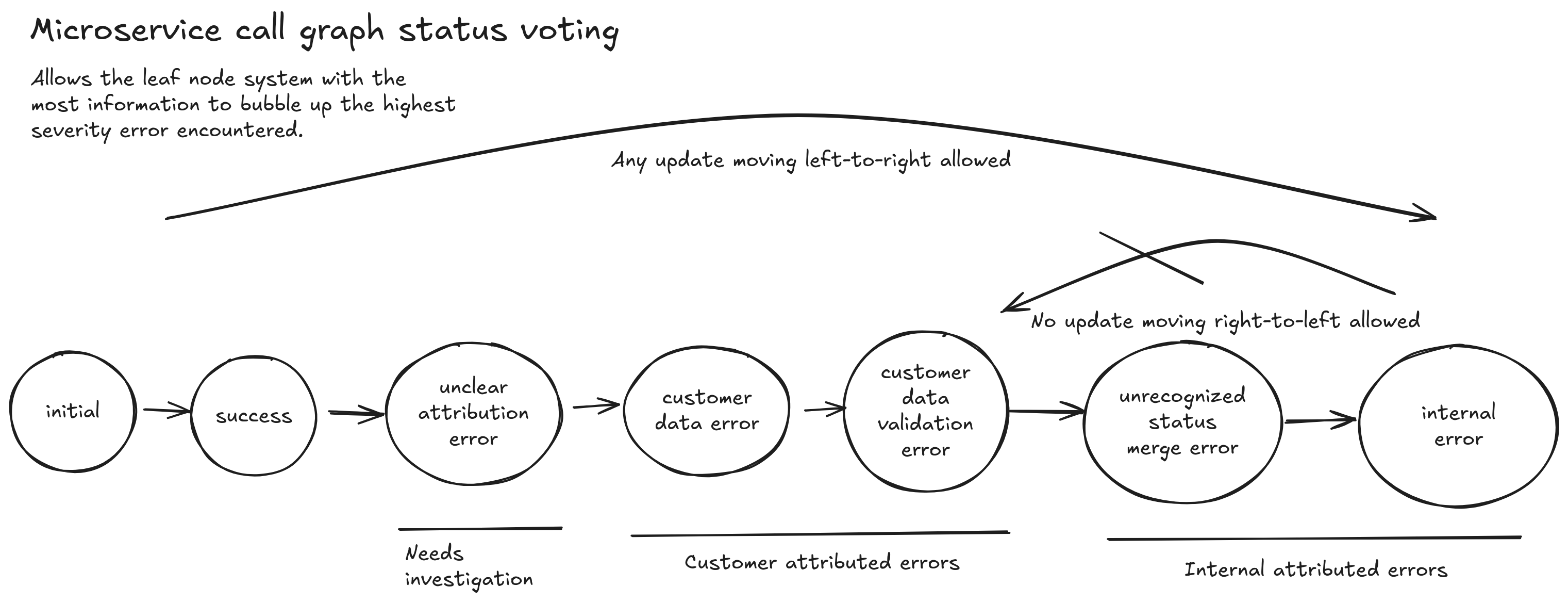

We need a voting algorithm to merge all reported statuses into a final status. That final status should favor severity first and specificity second. We can visualize this as settling into local minimums on a response surface plot.

- Customer errors are higher severity than successes. Internal errors are higher severity than customer errors.

- Customer errors are more specific than unclear attribution errors. Customer data validation errors are more specific than generic customer data errors.

This data flow diagram shows how state is updated inside each service as well as passed between services. I only show 5 services and a database, but this could scale to very large call graphs as the data added to the response remains a constant size.

The data flow looks similar to distributed tracing, but there are a couple of important differences. At scale, distributed tracing samples only a small percentage of requests, while this status reporting mechanism runs on every single request. Distributed tracing also passes IDs between services and then uploads trace data to a monitoring service by ID. This design just passes a value back in response headers or in a metadata section of the response body. Those two differences make this cost-effective to run on every request.

Feedback

What do you think? Should we just attach very explicit business meaning to HTTP codes? Does leaving them decoupled retain more flexibility for evolving classifications while keeping the system API stable? Are there existing standards or frameworks I can research that accomplish a similar objective?